Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

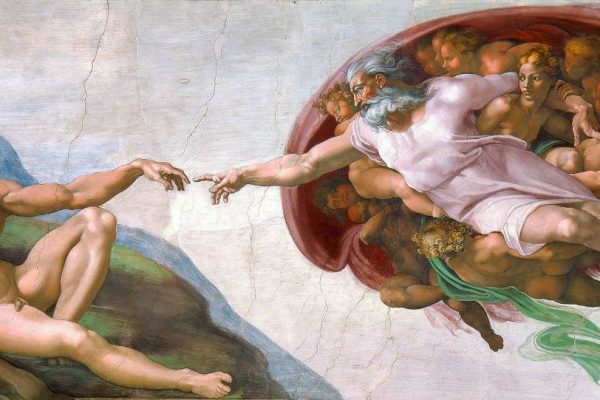

The famous School of Athens is a depiction of philosophy. The scene takes place in classical times, as both the architecture and the garments indicate. Figures representing each subject that must be mastered in order to hold a true philosophic debate – astronomy, geometry, arithmetic, and solid geometry – are depicted in concrete form. The arbiters of this rule, the main figures, Plato and Aristotle, are shown in the centre, engaged in such a dialogue. Plato is pointing to the heavens, indicating that the truth is found in the world of ideas, while Aristotle points to the earth, indicating that the truth is found through the experience of the senses. Raphael does not entrust his illustration to allegorical figures, as was customary in the 14th and 15th centuries. Rather, he groups the solemn figures of thinkers and philosophers together in a large, grandiose architectural framework. This framework is characterized by a high dome, a vault with lacunar ceiling and pilasters. It is probably inspired by late Roman architecture or – as most critics believe – by Bramante’s project for the new St. Peter’s which is itself a symbol of the synthesis of pagan and Christian philosophies.

The figures who dominate the composition do not crowd the environment, nor are they suffocated by it. Rather, they underline the breadth and depth of the architectural structures. The protagonists – Plato, represented with a white beard (some people identify this solemn old man with Leonardo da Vinci) and Aristotle – are both characterized by a precise and meaningful pose. Raphael’s descriptive capacity, in contrast to that visible in the allegories of earlier painters, is such that the figures do not pay homage to, or group around the symbols of knowledge; they do not form a parade. They move, act, teach, discuss and become excited. The painting celebrates classical thought, but it is also dedicated to the liberal arts, symbolized by the statues of Apollo and Minerva. Grammar, Arithmetic and Music are personified by figures located in the foreground, at left. Geometry and Astronomy are personified by the figures in the foreground, at right. Behind them stand characters representing Rhetoric and Dialectic.

Plato and Aristotle are standing in the centre of the picture at the head of the steps. Diogenes is lying carefree on the steps to show his philosophical attitude: he despised all material wealth and the lifestyle associated with it. Below on the right is a great block of stone whose significance is probably connected with the first epistle of St Peter. It symbolizes Christ, the “cornerstone” which the builders have rejected, which becomes a stumbling block and a “rock of offence” to the unbeliever.

Some of the ancient philosophers bear the features of Raphael’s contemporaries. Bramante is shown as Euclid (in the foreground, at right, leaning over a tablet and holding a compass). Leonardo is, as we said, probably shown as Plato. Francesco Maria Della Rovere appears once again near Bramante, dressed in white. Michelangelo, sitting on the stairs and leaning on a block of marble, is represented as an alone and melancholic Heraclitus. A close examination of the intonaco shows that Heraclitus was the last figure painted when the fresco was completed, in 1511. The allusion to Michelangelo is probably a gesture of homage to the artist, who had recently unveiled the frescoes of the Sistine Ceiling. Raphael – at the extreme right, with a dark hat – and his friend, Sodoma, are also present (they exemplify the glorification of the fine arts and they are posed on the same level as the liberal arts).

The fresco achieved immediate success. Its beauty and its thematic unity were universally accepted. The enthusiasm with which it was received was not marred by reservations, as was the public reaction to the Sistine Ceiling.