Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

The Basilica of Saint Peter, officially known in Italian as the Basilica di San Pietro in Vaticano and colloquially called Saint Peter’s Basilica, ranks second among the five major basilicas of Rome and its Vatican City enclave. Possibly the largest church in Christianity, it covers an area of 23,000 m² (5.7 acres) and has a capacity of over 60,000 people. One of the holiest sites of Christendom, it is the burial site of basilica namesake Saint Peter, who was one of the twelve apostles of Jesus, first Bishop of Antioch, and later first Bishop of Rome. Tradition holds that his tomb is below the baldachino and altar; for this reason, many Popes, starting with the first ones, have been buried there. The current basilica was started in 1506 and completed in 1626, and was built over the Constantinian basilica.

Although the Vatican basilica is not the Pope’s official ecclesiastical seat (Saint John Lateran), it is most certainly his principal church, as most Papal ceremonies take place at St. Peter’s due to its size, proximity to the Papal residence, and location within the Vatican City walls. The basilica also holds a relic of the Cathedra Petri, the episcopal throne of the basilica’s namesake when he led the Roman church, but which is no longer used as the Papal cathedra.

The current location is probably the site of the Circus of Nero, where Saint Peter was buried upon dying on an inverted cross (tradition states Saint Peter was crucified at the site of the Tempietto) in AD 64. After Constantine I officially recognised Christianity, he started construction in 324 of a great basilica in this exact spot, which had previously been a cemetery for pagans as well as Christians.

In 846, Arabs looted all the gold and silver that Pope Hadrian I had decorated the basilica with: silver plates on the floors, golden ones on the walls, and a golden balustrade weighing over half a ton. Pope Leo IV started work on the Leonine walls of Rome in response to this attack.

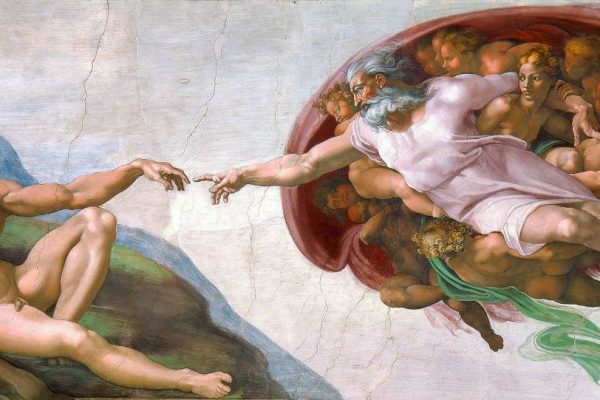

Old St. Peter’s was in many ways a typical early basilica-plan church, with a nave and two aisles. The crossing was above the altar, producing a “T” plan. The importance of the shrine to St Peter soon led to its design being copied, for instance at the Basilica di Santa Prassede. Over the years it was richly decorated with the wealth brought by the flow of pilgrims, but by the mid-15th century the south wall was in danger of collapse and it was decided that the basilica should be rebuilt. Pope Nicholas V asked architect Bernardo Rossellino to start adding to the old church. This was abandoned after a short while. In the late 15th century Pope Sixtus IV had the Sistine Chapel started nearby.

The basilica in itself is a work of art composed of many valuable artistic elements. Construction started under Pope Julius II in 1505, and was completed in 1615 under Pope Paul V. Donato Bramante was to be the first chief architect. Many famous artists worked on the “Fabbrica di San Pietro” (as the complex of building operations were officially called). Michelangelo, who served as main architect for a while, designed the dome. After the death of Julius II, building was halted until Pope Paul III asked Michelangelo to design the rest of the church. After Michelangelo’s death his student Giacomo della Porta continued with the unfinished portions of the church. Carlo Maderno became the chief architect later on, and designed the entrance.

In 1939, workers renovating the grottoes beneath St. Peter’s, the traditional burial area of the popes, made a stunning find. Just below the floor level, they discovered an ancient Roman grave. It soon became clear that there wasn’t just one grave, but an entire city of the dead. After many months of digging, the excavators came to a section of older graves, near the area underneath the high altar. Directly beneath the altar, they found a large burial site and a wall painted red. In a niche connected to that wall, they found the bones of a man. Nearly 30 years later, in 1968, Pope Paul VI announced that those bones belonged to St. Peter[1].

St. Peter’s Square

Directly to the east of the church is St. Peter’s Square (Piazza San Pietro), built between 1656 and 1667. It is surrounded by an elliptical colonnade with two pairs of Doric columns which form its breadth, each bearing Ionic entablatures. This is an excellent example of Baroque architecture, where creativity is coupled with flexible guidelines. In the center of the colonnade, which was designed by Bernini, is a 25.5 m (83.6 ft) tall obelisk. The obelisk was moved to its present location in 1585 by order of Pope Sixtus V. The obelisk dates back to the 13th century BC in Egypt, and was moved to Rome in the 1st century to stand in Nero’s Circus some 250 m (820 ft) away. Including the cross on top and the base the obelisk reaches 40 m (131 ft). On top of the obelisk there used to be a large bronze globe allegedly containing the ashes of Julius Caesar. This was removed when the obelisk was erected in St. Peter’s Square. There are also two fountains in the square, the south one by Maderno (1613) and the northern one by Bernini (1675).

The dome

The dome designed by Michelangelo was completed by Giacomo della Porta in 1590.The dome, or cupola, was designed by Michelangelo, who became chief architect in 1546. At the time of his death (1564), the dome was finished as far as the drum, the base on which a dome sits. The dome was vaulted between 1585 and 1590 by the architect Giacomo della Porta with the assistance of Domenico Fontana, who was probably the best engineer of the day. Fontana built the lantern the following year, and the ball was placed in 1593.

A view of Michelangelo’s domeAs built, the double dome is brick, 42.3 m (138.8 ft) in interior diameter (almost as large as the Pantheon), rising to 120 m (394 ft) above the floor. In the mid-18th century, cracks appeared in the dome, so four iron chains were installed between the two shells to bind it, like the rings that keep a barrel from bursting. (Visitors who climb the spiral stairs between the dome shells can glimpse them.) The four piers of the crossing that support it are each 18 metres (59 ft) across. It is not simply its vast scale (136.57 m or 448.06 ft from the floor of the church to the top of the added cross) that makes it extraordinary . Michelangelo’s dome is not a hemisphere, but a paraboloid: it has a vertical thrust, which is made more emphatic by the bold ribbing that springs from the paired Corinthian columns, which appear to be part of the drum, but which stand away from it like buttresses, to absorb the outward thrust of the dome’s weight. The grand arched openings just visible in the illustration but normally invisible to viewers below, enable access (but not to the public) all around the base of the drum; they are dwarfed by the monumental scale of their surroundings. Above, the vaulted dome rises to Fontana’s two-stage lantern, capped with a spire.

The egg-shaped dome exerts less outward thrust than a lower hemispheric one (such as Mansart’s at Les Invalides) would have done. The dome conceived by Donato Bramante at the outset in 1503 was planned to be carried out with a single masonry shell, a plan discovered to be infeasible. San Gallo came up with the double shell, and Michelangelo improved upon it. The piers at the crossing, which were the first masonry to be laid, and which were intended to support the original dome, were a constant concern, too slender in Bramante’s plan, they were redesigned several times as the dome plans evolved.

Other domes around the world, built since, are always compared to this one which served as model: Saint Joseph’s Oratory in Montreal, Quebec, St Paul’s Cathedral in London, Les Invalides in Paris, United States Capitol in Washington, DC, Harrisburg, PA , and the more literal reproduction at the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro, Cote d’Ivoire.

Entrances

Above the main entrance is the inscription IN HONOREM PRINCIPIS APOST PAVLVS V BVRGHESIVS ROMANVS PONT MAX AN MDCXII PONT VII (In honor of the prince of apostles; Paul V, citizen of Rome, Supreme Pontiff, in the year 1612 and the seventh year of his pontificate).

The façade is 114.69 metres (376.28 ft) wide and 45.55 m (149.44ft) high. On top are statues of Christ, John the Baptist, and eleven of the apostles; St. Peter’s statue is inside. Two clocks are on either side of the top, the one on the left has been operated electrically since 1931, its oldest bell dating to 1288.

Between the façade and the interior is the portico. Mainly designed by Maderno, it contains an 18th century statue of Charlemagne by Cornacchini to the south, and an equestrian sculpture of Emperor Constantine by Bernini (1670) to the north. The southernmost door, designed by Giacomo Manzù, is called the “Door of the Dead”. The door in the center is by Antonio Averulino (1455), and preserved from the previous basilica.

The northernmost door is the “Holy Door” in bronze by Vico Consorti (1950), which is by tradition, only opened for great celebrations such as Jubilee years. Above it are inscriptions, the top reading PAVLVS V PONT MAX ANNO XIII, and the one just above the door reading GREGORIVS XIII PONT MAX. In between are white slabs commemorating the most recent openings.

Interior

Walking along the right aisle of the basilica, there are several noteworthy monuments and memorials. The first is Michelangelo’s Pietà, located immediately to the right of the entrance. After an incident in 1972 when an individual damaged it with an axe, the sculpture was placed behind protective glass. Up the aisle is the monument of Queen Christina of Sweden, who abdicated in 1654 in order to convert to Catholicism. Further up are the monuments of popes Pius XI and Pius XII, as well as the altar of St Sebastian. Even further up is the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, which is open during religious services only. Inside it is a tabernacle on the altar resembling Bramante’s Tempietto at San Pietro in Montorio. Bernini sculpted this gilded bronze tabernacle in 1674. The two kneeling angels were added later. Further still are the monuments of popes Gregory XIII (completed in 1723 by Carlo Rusconi) and Gregory XIV.

In the northwestern corner of the nave sits the statue of St. Peter Enthroned, attributed to late 13th century sculptor Arnolfo di Cambio (with some scholars dating it back to the 5th century). The foot of the statue is eroded due to centuries of pilgrims kissing it. Along the floor of the nave are markers with the comparative lengths of other churches, starting from the entrance (not an original detail). Along the pilasters are niches housing 39 statues of saints who founded religious orders.

Walking down the left aisle there is the Altar of Transfiguration. Walking down towards the entrance are the monuments to Leo XI and Innocent XI followed by the Chapel of the Immaculate Virgin Mary. After that come the monuments to Pius X and Innocent VIII, then the monuments to John XXIII and Benedict XV, and the Chapel of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin. After that comes the Monument to the Royal Stuarts, directly opposite the one to Maria Clementina Sobieska. Symmetrically, the two monarchs who gave up their thrones for their Catholic faith in the 17th century, are honored side by side in the most important church in Catholicism. Finally, right before the end of the church, is the Baptistry.

The right transept contains three altars, of St. Wenceslas, St. Processo and St. Martiniano, and St. Erasmus. The left transept also contains three altars, that of St. Peter’s Crucifixion, St. Joseph and St. Thomas. West of the left transept is the monument to Alexander VII by Bernini. A skeleton lifts a fold of red marble drapery and holds an hourglass symbolising the inevitability of death. He is flanked on the right by a statue representing religion, who holds her foot atop a globe, with a thorn piercing her toe from the British Isles, symbolizing the pope’s problems with the Church of England.

Over the main altar stands a 30 m (98 ft) tall baldachin held by four immense pillars, all designed by Bernini between 1624 and 1632. The baldachin was built to fill the space beneath the cupola, and it is said that the bronze used to make it was taken from the Pantheon. (It is also said that it is the largest bronze piece in the world.) Underneath the baldachin is the traditional tomb of St. Peter. In the four corners surrounding the baldachin are statues of St Helena (northwest, holding a large cross in her right hand, by Andrea Bolgi), St Longinus (northeast, holding his spear in his right hand, by Bernini in 1639), St Andrew (southeast, spread upon the cross which bears his name, by Francois Duquesnoy) and St Veronica (southwest, holding her veil, by Francesco Mochi). Each of these statues represents a relic associated with the person, respectively, a piece of The Cross, the Spear of Destiny, St Andrew’s head (as well as part of his cross) and Veronica’s Veil. In 1964, St Andrew’s head was returned to the Greek Orthodox Church by the Pope. It should be noted that the Vatican makes no claims as to the authenticity of several of these relics, and in fact other Catholic churches also possess “the same” relics. Along the base of the inside of the dome is written, in letters 2 m (6.5 ft) high, TV ES PETRVS ET SVPER HANC PETRAM AEDIFICABO ECCLESIAM MEAM. TIBI DABO CLAVES REGNI CAELORVM (Vulgate, from Matthew 16:18-19; “…you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church. … I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven….”). Near the top of the dome is another, smaller, circular inscription: S. PETRI GLORIAE SIXTVS PP. V. A. M. D. XC. PONTIF. V. (To the glory of St. Peter; Sixtus V, pope, in the year 1590 and the fifth year of his pontificate).

The Burial of St. Petronilla is an altarpiece painted by Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (Guercini) in 1623. It simultaneously depicts the burial and the welcoming to heaven of the martyred St. Petronilla. The altar is dedicated to the saint, and contains her relics.

The Chair of Saint Peter, Cathedra Petri, is behind the altar in the basilica apse.At the apse of the church is the Triumph of the Chair of Saint Peter (1666) by Bernini, a focus of the Feast of Cathedra Petri celebrated annually on February 22 in accordance to the calendar of saints. The triumph is topped by a yellow window in which is a dove, portraying the Holy Spirit, surrounded by twelve rays, symbolising the apostles. Beneath it is the bronze encasing of the relic of the chair of St. Peter, given to the Vatican from Charles the Bald in 875. To the right of the chair are St Ambrose and St Augustine (fathers of the Latin church), and to the left are St Athanasius and St John Chrysostom (fathers of the Greek church). Further to the right is the monument to Urban VIII, by Bernini, and further to the left is the monument to Paul III.

The Basilica of Saint Peter, officially known in Italian as the Basilica di San Pietro in Vaticano and colloquially called Saint Peter’s Basilica, ranks second among the five major basilicas of Rome and its Vatican City enclave. Possibly the largest church in Christianity, it covers an area of 23,000 m² (5.7 acres) and has a capacity of over 60,000 people. One of the holiest sites of Christendom, it is the burial site of basilica namesake Saint Peter, who was one of the twelve apostles of Jesus, first Bishop of Antioch, and later first Bishop of Rome. Tradition holds that his tomb is below the baldachino and altar; for this reason, many Popes, starting with the first ones, have been buried there. The current basilica was started in 1506 and completed in 1626, and was built over the Constantinian basilica.

Although the Vatican basilica is not the Pope’s official ecclesiastical seat (Saint John Lateran), it is most certainly his principal church, as most Papal ceremonies take place at St. Peter’s due to its size, proximity to the Papal residence, and location within the Vatican City walls. The basilica also holds a relic of the Cathedra Petri, the episcopal throne of the basilica’s namesake when he led the Roman church, but which is no longer used as the Papal cathedra.

The current location is probably the site of the Circus of Nero, where Saint Peter was buried upon dying on an inverted cross (tradition states Saint Peter was crucified at the site of the Tempietto) in AD 64. After Constantine I officially recognised Christianity, he started construction in 324 of a great basilica in this exact spot, which had previously been a cemetery for pagans as well as Christians.

In 846, Arabs looted all the gold and silver that Pope Hadrian I had decorated the basilica with: silver plates on the floors, golden ones on the walls, and a golden balustrade weighing over half a ton. Pope Leo IV started work on the Leonine walls of Rome in response to this attack.

Old St. Peter’s was in many ways a typical early basilica-plan church, with a nave and two aisles. The crossing was above the altar, producing a “T” plan. The importance of the shrine to St Peter soon led to its design being copied, for instance at the Basilica di Santa Prassede. Over the years it was richly decorated with the wealth brought by the flow of pilgrims, but by the mid-15th century the south wall was in danger of collapse and it was decided that the basilica should be rebuilt. Pope Nicholas V asked architect Bernardo Rossellino to start adding to the old church. This was abandoned after a short while. In the late 15th century Pope Sixtus IV had the Sistine Chapel started nearby.

The basilica in itself is a work of art composed of many valuable artistic elements. Construction started under Pope Julius II in 1505, and was completed in 1615 under Pope Paul V. Donato Bramante was to be the first chief architect. Many famous artists worked on the “Fabbrica di San Pietro” (as the complex of building operations were officially called). Michelangelo, who served as main architect for a while, designed the dome. After the death of Julius II, building was halted until Pope Paul III asked Michelangelo to design the rest of the church. After Michelangelo’s death his student Giacomo della Porta continued with the unfinished portions of the church. Carlo Maderno became the chief architect later on, and designed the entrance.

In 1939, workers renovating the grottoes beneath St. Peter’s, the traditional burial area of the popes, made a stunning find. Just below the floor level, they discovered an ancient Roman grave. It soon became clear that there wasn’t just one grave, but an entire city of the dead. After many months of digging, the excavators came to a section of older graves, near the area underneath the high altar. Directly beneath the altar, they found a large burial site and a wall painted red. In a niche connected to that wall, they found the bones of a man. Nearly 30 years later, in 1968, Pope Paul VI announced that those bones belonged to St. Peter[1].

St. Peter’s Square

Directly to the east of the church is St. Peter’s Square (Piazza San Pietro), built between 1656 and 1667. It is surrounded by an elliptical colonnade with two pairs of Doric columns which form its breadth, each bearing Ionic entablatures. This is an excellent example of Baroque architecture, where creativity is coupled with flexible guidelines. In the center of the colonnade, which was designed by Bernini, is a 25.5 m (83.6 ft) tall obelisk. The obelisk was moved to its present location in 1585 by order of Pope Sixtus V. The obelisk dates back to the 13th century BC in Egypt, and was moved to Rome in the 1st century to stand in Nero’s Circus some 250 m (820 ft) away. Including the cross on top and the base the obelisk reaches 40 m (131 ft). On top of the obelisk there used to be a large bronze globe allegedly containing the ashes of Julius Caesar. This was removed when the obelisk was erected in St. Peter’s Square. There are also two fountains in the square, the south one by Maderno (1613) and the northern one by Bernini (1675).

The dome

The dome designed by Michelangelo was completed by Giacomo della Porta in 1590.The dome, or cupola, was designed by Michelangelo, who became chief architect in 1546. At the time of his death (1564), the dome was finished as far as the drum, the base on which a dome sits. The dome was vaulted between 1585 and 1590 by the architect Giacomo della Porta with the assistance of Domenico Fontana, who was probably the best engineer of the day. Fontana built the lantern the following year, and the ball was placed in 1593.

A view of Michelangelo’s domeAs built, the double dome is brick, 42.3 m (138.8 ft) in interior diameter (almost as large as the Pantheon), rising to 120 m (394 ft) above the floor. In the mid-18th century, cracks appeared in the dome, so four iron chains were installed between the two shells to bind it, like the rings that keep a barrel from bursting. (Visitors who climb the spiral stairs between the dome shells can glimpse them.) The four piers of the crossing that support it are each 18 metres (59 ft) across. It is not simply its vast scale (136.57 m or 448.06 ft from the floor of the church to the top of the added cross) that makes it extraordinary . Michelangelo’s dome is not a hemisphere, but a paraboloid: it has a vertical thrust, which is made more emphatic by the bold ribbing that springs from the paired Corinthian columns, which appear to be part of the drum, but which stand away from it like buttresses, to absorb the outward thrust of the dome’s weight. The grand arched openings just visible in the illustration but normally invisible to viewers below, enable access (but not to the public) all around the base of the drum; they are dwarfed by the monumental scale of their surroundings. Above, the vaulted dome rises to Fontana’s two-stage lantern, capped with a spire.

The egg-shaped dome exerts less outward thrust than a lower hemispheric one (such as Mansart’s at Les Invalides) would have done. The dome conceived by Donato Bramante at the outset in 1503 was planned to be carried out with a single masonry shell, a plan discovered to be infeasible. San Gallo came up with the double shell, and Michelangelo improved upon it. The piers at the crossing, which were the first masonry to be laid, and which were intended to support the original dome, were a constant concern, too slender in Bramante’s plan, they were redesigned several times as the dome plans evolved.

Other domes around the world, built since, are always compared to this one which served as model: Saint Joseph’s Oratory in Montreal, Quebec, St Paul’s Cathedral in London, Les Invalides in Paris, United States Capitol in Washington, DC, Harrisburg, PA , and the more literal reproduction at the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro, Cote d’Ivoire.

Entrances

Above the main entrance is the inscription IN HONOREM PRINCIPIS APOST PAVLVS V BVRGHESIVS ROMANVS PONT MAX AN MDCXII PONT VII (In honor of the prince of apostles; Paul V, citizen of Rome, Supreme Pontiff, in the year 1612 and the seventh year of his pontificate).

The façade is 114.69 metres (376.28 ft) wide and 45.55 m (149.44ft) high. On top are statues of Christ, John the Baptist, and eleven of the apostles; St. Peter’s statue is inside. Two clocks are on either side of the top, the one on the left has been operated electrically since 1931, its oldest bell dating to 1288.

Between the façade and the interior is the portico. Mainly designed by Maderno, it contains an 18th century statue of Charlemagne by Cornacchini to the south, and an equestrian sculpture of Emperor Constantine by Bernini (1670) to the north. The southernmost door, designed by Giacomo Manzù, is called the “Door of the Dead”. The door in the center is by Antonio Averulino (1455), and preserved from the previous basilica.

The northernmost door is the “Holy Door” in bronze by Vico Consorti (1950), which is by tradition, only opened for great celebrations such as Jubilee years. Above it are inscriptions, the top reading PAVLVS V PONT MAX ANNO XIII, and the one just above the door reading GREGORIVS XIII PONT MAX. In between are white slabs commemorating the most recent openings.

Interior

Walking along the right aisle of the basilica, there are several noteworthy monuments and memorials. The first is Michelangelo’s Pietà, located immediately to the right of the entrance. After an incident in 1972 when an individual damaged it with an axe, the sculpture was placed behind protective glass. Up the aisle is the monument of Queen Christina of Sweden, who abdicated in 1654 in order to convert to Catholicism. Further up are the monuments of popes Pius XI and Pius XII, as well as the altar of St Sebastian. Even further up is the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, which is open during religious services only. Inside it is a tabernacle on the altar resembling Bramante’s Tempietto at San Pietro in Montorio. Bernini sculpted this gilded bronze tabernacle in 1674. The two kneeling angels were added later. Further still are the monuments of popes Gregory XIII (completed in 1723 by Carlo Rusconi) and Gregory XIV.

In the northwestern corner of the nave sits the statue of St. Peter Enthroned, attributed to late 13th century sculptor Arnolfo di Cambio (with some scholars dating it back to the 5th century). The foot of the statue is eroded due to centuries of pilgrims kissing it. Along the floor of the nave are markers with the comparative lengths of other churches, starting from the entrance (not an original detail). Along the pilasters are niches housing 39 statues of saints who founded religious orders.

Walking down the left aisle there is the Altar of Transfiguration. Walking down towards the entrance are the monuments to Leo XI and Innocent XI followed by the Chapel of the Immaculate Virgin Mary. After that come the monuments to Pius X and Innocent VIII, then the monuments to John XXIII and Benedict XV, and the Chapel of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin. After that comes the Monument to the Royal Stuarts, directly opposite the one to Maria Clementina Sobieska. Symmetrically, the two monarchs who gave up their thrones for their Catholic faith in the 17th century, are honored side by side in the most important church in Catholicism. Finally, right before the end of the church, is the Baptistry.

The right transept contains three altars, of St. Wenceslas, St. Processo and St. Martiniano, and St. Erasmus. The left transept also contains three altars, that of St. Peter’s Crucifixion, St. Joseph and St. Thomas. West of the left transept is the monument to Alexander VII by Bernini. A skeleton lifts a fold of red marble drapery and holds an hourglass symbolising the inevitability of death. He is flanked on the right by a statue representing religion, who holds her foot atop a globe, with a thorn piercing her toe from the British Isles, symbolizing the pope’s problems with the Church of England.

Over the main altar stands a 30 m (98 ft) tall baldachin held by four immense pillars, all designed by Bernini between 1624 and 1632. The baldachin was built to fill the space beneath the cupola, and it is said that the bronze used to make it was taken from the Pantheon. (It is also said that it is the largest bronze piece in the world.) Underneath the baldachin is the traditional tomb of St. Peter. In the four corners surrounding the baldachin are statues of St Helena (northwest, holding a large cross in her right hand, by Andrea Bolgi), St Longinus (northeast, holding his spear in his right hand, by Bernini in 1639), St Andrew (southeast, spread upon the cross which bears his name, by Francois Duquesnoy) and St Veronica (southwest, holding her veil, by Francesco Mochi). Each of these statues represents a relic associated with the person, respectively, a piece of The Cross, the Spear of Destiny, St Andrew’s head (as well as part of his cross) and Veronica’s Veil. In 1964, St Andrew’s head was returned to the Greek Orthodox Church by the Pope. It should be noted that the Vatican makes no claims as to the authenticity of several of these relics, and in fact other Catholic churches also possess “the same” relics. Along the base of the inside of the dome is written, in letters 2 m (6.5 ft) high, TV ES PETRVS ET SVPER HANC PETRAM AEDIFICABO ECCLESIAM MEAM. TIBI DABO CLAVES REGNI CAELORVM (Vulgate, from Matthew 16:18-19; “…you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church. … I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven….”). Near the top of the dome is another, smaller, circular inscription: S. PETRI GLORIAE SIXTVS PP. V. A. M. D. XC. PONTIF. V. (To the glory of St. Peter; Sixtus V, pope, in the year 1590 and the fifth year of his pontificate).

The Burial of St. Petronilla is an altarpiece painted by Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (Guercini) in 1623. It simultaneously depicts the burial and the welcoming to heaven of the martyred St. Petronilla. The altar is dedicated to the saint, and contains her relics.

The Chair of Saint Peter, Cathedra Petri, is behind the altar in the basilica apse.At the apse of the church is the Triumph of the Chair of Saint Peter (1666) by Bernini, a focus of the Feast of Cathedra Petri celebrated annually on February 22 in accordance to the calendar of saints. The triumph is topped by a yellow window in which is a dove, portraying the Holy Spirit, surrounded by twelve rays, symbolising the apostles. Beneath it is the bronze encasing of the relic of the chair of St. Peter, given to the Vatican from Charles the Bald in 875. To the right of the chair are St Ambrose and St Augustine (fathers of the Latin church), and to the left are St Athanasius and St John Chrysostom (fathers of the Greek church). Further to the right is the monument to Urban VIII, by Bernini, and further to the left is the monument to Paul III.